Introduction

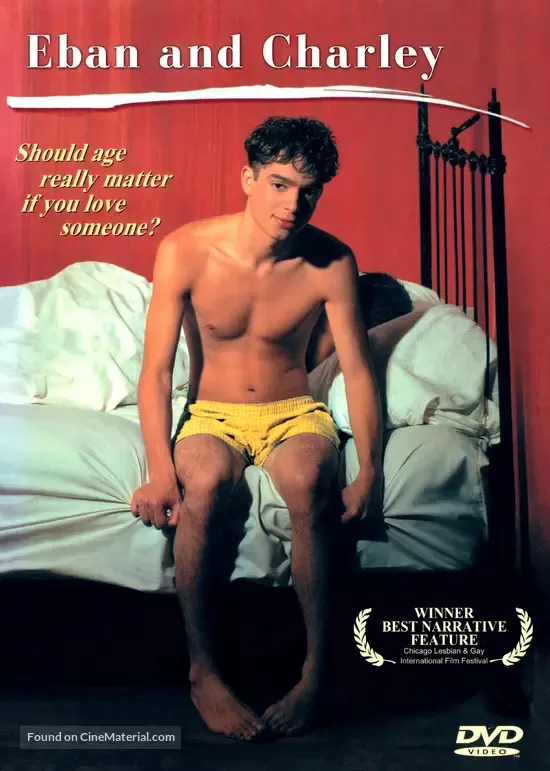

“Eban and Charley” isn’t your run-of-the-mill love story—it’s the kind of film that tiptoes along the edge of controversy, daring you to look away but making it nearly impossible. Directed by James Bolton and released in 2000, this indie drama stirred up plenty of debate when it first hit the festival circuit. The story zeroes in on a relationship between a 29-year-old man and a 15-year-old boy, set against the rainy, introspective backdrop of the Pacific Northwest. If you’re expecting melodrama or heavy-handed moralizing, think again. Bolton’s approach is subdued, almost detached, letting the audience wrestle with their own feelings about what unfolds on screen. I remember stumbling across the DVD cover, which oddly features only Charley—almost as if the film itself is inviting us to focus on innocence, or perhaps to question whose story this really is.

Review

Tackling a subject as fraught as this is like walking a tightrope in a windstorm. The filmmakers here don’t preach, nor do they sensationalize; instead, they present Eban and Charley’s relationship in a matter-of-fact way, leaving us to stew in our own discomfort. There’s a muted quality to the storytelling, as if the camera itself is unsure how close it should get. Personally, I found myself torn—my heart tugged in one direction, my mind yanking me back in another. Is this forbidden love, or something much darker? The film doesn’t spoon-feed us an answer.

Eban, played with a sort of gentle ambiguity, returns to his hometown from Seattle for Christmas. His reasons are hazy, like fog rolling in off the coast. Wandering through local shops, he crosses paths with Charley—a handsome, lonely 15-year-old who’s still reeling from his mother’s death. Their friendship blooms quickly, under the pretense of guitar lessons and shared solitude. I couldn’t help but notice how Eban’s attention seems to fill a void in Charley’s life, the way sunlight might sneak through a crack in the blinds. They ride bikes, stroll along the beach, and eventually, in a moment that feels both tender and unsettling, Charley makes the first move. They cuddle and kiss, but neither seems fully aware of the consequences swirling around them.

The tension ratchets up when Charley’s father interrupts a sleepover, and Eban’s own father steps in with a warning. We learn that Eban has a history—he lost his job over an affair with a young student. His father’s words are heavy, almost thunderous: if Eban doesn’t change, he’ll call the police himself. Eban tries to pull away, but Charley clings to the promises made. The story spirals toward its conclusion, with the pair running away together, leaving behind a trail of unanswered questions.

What struck me most was the film’s refusal to paint anyone as a villain or a victim. There’s no explicit sexual content, save for one mild, semi-clothed scene, which somehow makes the whole thing feel even more ambiguous. I found myself asking: is Charley simply desperate for love, or is he being manipulated? Eban’s motives are murky—does he truly care for Charley, or is he repeating a dangerous pattern? The film doesn’t offer easy answers, and maybe that’s the point.

Shot in a raw, home-video style, the movie has an indie vibe that’s both intimate and a little rough around the edges. The performances are solid—nothing Oscar-worthy, but believable enough to pull you into their world. I’ll admit, the pacing is slow, almost languid, so if you’re looking for fireworks, you might need to bring some patience. For me, watching “Eban and Charley” felt a bit like standing in the rain: uncomfortable, sometimes cold, but strangely compelling.

In the end, this is one of those films that lingers, gnawing at the edges of your thoughts. It’s not for everyone, and honestly, I’m still not sure how I feel about it. But if you’re willing to grapple with the gray areas of love, loneliness, and morality, it’s worth a look—just don’t expect to walk away with easy answers.

The DVD cover focusing only on Charley made me pause—it’s such a subtle but loaded choice. I wonder how that decision shapes viewers’ initial assumptions about innocence or guilt. The detached storytelling you mentioned makes sense; it’s like the film trusts us to grapple without hand-holding.