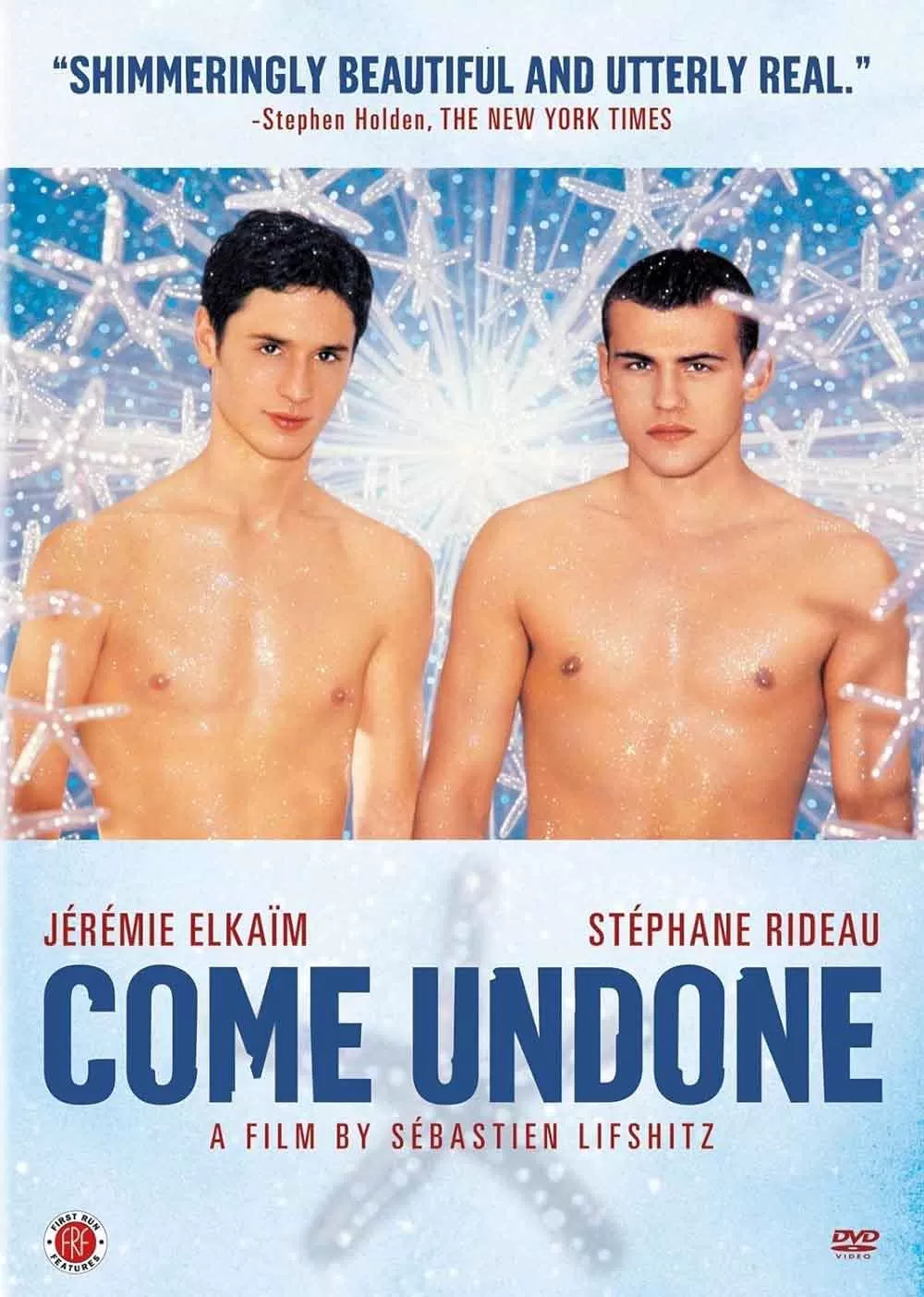

Summer romances aren’t always carefree affairs. Some leave profound emotional wounds, as depicted in Come Undone.

The film presents a striking contrast between idyllic coastal scenes – sun, sea, bare-chested youths, starry nights – and the crushing weight of depression. These seemingly incompatible elements form the essence of Presque Rien (Almost Nothing in English).

Seventeen-year-old Marc arrives at the French seaside with his fractured family. Far from being a relaxing getaway, this vacation unfolds against a backdrop of tragedy. His brother’s death has left his mother emotionally absent, while his sister struggles to maintain family cohesion. Marc shoulders these burdens along with his own awakening desires – physical urges he barely comprehends.

Enter Chédan: older, self-assured, bronzed by the sun, embodying freedom. Their connection develops rapidly – physical, uncertain, and raw. Dialogue remains sparse, replaced by tentative touches, lingering gazes, and unspoken longing.

The narrative mirrors the nonlinear nature of grief, shifting between the fateful summer and subsequent months when Marc relocates, attempting to hold himself together. He leaves behind his home, family, and possibly the boy he loved – yet carries an inescapable emotional weight.

The film resists tidy resolutions, offering no closure. This refusal to simplify reality constitutes its greatest honesty.

Notable for its restraint, the production features no manipulative musical cues or expository narration. Intimate moments unfold in silence – just breath, sweat, and stolen glances. The effect resembles confronting a painful memory before one is ready.

Sexual encounters are portrayed with unflinching authenticity – sometimes gentle, sometimes uncomfortable, never sensationalized. As Marc navigates first experiences of desire and heartbreak, viewers share his visceral confusion.

Depression emerges as the story’s unseen protagonist. Beyond romance, this is a study of emotional disintegration. Marc’s anguish manifests not as poetic melancholy but as debilitating paralysis.

The film’s refusal to romanticize mental illness gives it particular significance. It captures the isolating numbness and disorder of depression with rare clarity.

A pivotal moment occurs when Marc confesses: “I’m doing what you said.” This simple statement reveals a lifetime spent meeting others’ expectations. His tentative steps toward self-discovery prove more painful than anticipated.

The conclusion defies conventional storytelling. There’s no dramatic resolution or romantic reconciliation. Marc doesn’t emerge transformed or whole.

Yet he persists. And in this endurance, he begins – perhaps for the first time – to truly feel. Sometimes, that fragile awakening transcends being “almost nothing.”